Listening to Tuesday’s argument in Fourth Estate Public Benefit Corp. v. Wall-Street.com, it was striking that most of the justices would rather have been somewhere else, or at least deciding some other case. Maybe a trademark a case (see below)? Ironically, the justice with the most interest in the rights of copyright owners, Justice Ginsburg, was absent from oral argument recovering from surgery. But sometimes, even Supreme Court justices need to eat their vegetables.

Fourth Estate is exactly the kind of case that the Court should take. True enough, the policy issues are not earth shattering, the statutory interpretation issues are a little dull, and the controversy is so copyright-specific that it has no real implications for other areas of law. However, it is ridiculous in a national copyright system that the Fifth and Ninth Circuits allow copyright claimants to file a lawsuit based merely on filing an application for registration, whereas the other circuits require an actual registration or a rejection thereof (i.e., a decision on whether the work is copyrightable). This is a significant difference because the process takes several months on average.

Text likely to win over policy

Oral argument saw Petitioner’s flimsy statutory interpretation and more sympathetic policy position pitted against Respondent’s strong textual argument and less compelling policy stance (discussed in more detail below). If the justices were voting on their policy views alone, this case would probably be 9:0 or 8:1 in favor of Petitioner, but Respondent will be hoping that the law still matters. The tension between law and policy resulted in mostly even handed questioning at oral argument; as a consequence any predictions based on transcript metrics are quite speculative.

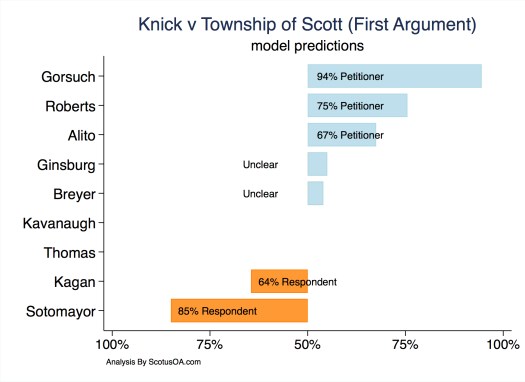

As the figure above shows, we predict Justices Kagan and Sotomayor, as well as the Chief Justice, to vote with Respondent. Justices Thomas and Alito (both silent during oral argument) will probably join them, as will Justice Breyer. A three-justice minority would not be surprising (based on the argument and Ginsburg’s history of favoring copyright owner interests), but the outcome is more likely to be 9:0 for Respondent (perhaps 8:1 with Ginsburg dissenting).

Ultimately, we predict that in this case at least, a straightforward reading of statute will carry the day.

How clear is the textual argument?

The issue in Fourth Estate is the correct reading of Section 411(a) of the Copyright Act, entitled “Registration and civil infringement actions.”

In simple terms, the most natural reading of the section is that it bars a copyright owner from instituting an infringement action until the Register of Copyrights (i.e., the Copyright Office) has either approved or refused registration. The relevant text of the section consists of three sentences. The first sentence reads:

… no civil action for infringement of the copyright in any United States work shall be instituted until preregistration or registration of the copyright claim has been made in accordance with this title.

The second sentence provides that if “the deposit, application, and fee required for registration have been delivered to the Copyright Office in proper form and registration has been refused” the applicant may then institute its civil action. The third sentence allows the Register of Copyrights to join in that litigation and defend its refusal.

Petitioner argued heroically that “registration … has been made” means simply that the copyright claimant has submitted an application in proper form to the Copyright Office. This is hard to square with the second sentence that talks about a registration having been refused. Basically, Petitioner wants “registration … has been made” to mean the exact same thing as the following 18 words from the second sentence: “the deposit, application, and fee required for registration have been delivered to the Copyright Office in proper form.” This requires the Court to treat the same word, registration, as meaning vastly different things from one sentence to the next; it also asks it to accept that vastly different expressions within the same section mean the same thing. This is both counter-intuitive and anti-canon.

The policy question is not clear-cut

The policy question in Fourth Estate is more finely balanced. Petitioner’s best argument was that being forced to wait several months for a registration to either be granted or denied puts the value of their copyrights at risk and denies them the chance to take swift injunctive action. This clearly scored some points with a few of the justices, particularly Justice Kavanaugh, who demanded a drawn out explanation.

However, Respondent and the Deputy Solicitor General did a good job explaining why such dramatic unfairness was unlikely in view of the availability of preregistration and expedited review (special handling). They also explained how registration as a precondition to litigation plays an important role in encouraging timely registration with the Copyright Office and deposit with the Library of Congress.

Copyright and trademark are not the same

For intellectual property lawyers who are bemused, enraged, or amused by the inability of non-specialists to understand the difference between copyright, trademark, and patent (it is like confusing Star Wars with Star Trek, or Lost In Space), the oral argument provided a couple of triggering exchanges:

John G. Roberts, Jr.

Well, that’s enough assuming that the registrar has registered the mark.

Aaron M. Panner

Again, the registrar does not have to register the mark.

The — the — not the mark, the copyright. …

John G. Roberts, Jr.

So you could go back, the registrar hasn’t even registered the mark, and you can go into court and say, hey, I get the benefits of having registered my mark?

Aaron M. Panner

The copyright claim, yes, Your Honor.

Prediction

Petitioner: Sotomayor, Kagan, Roberts, Breyer, Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Ginsburg

Respondent: none

Most likely to switch: Ginsburg, Kavanaugh, Gorsuch

You must be logged in to post a comment.