“We are all textualists now, [when it suits us]”

When a case is really close, really close, on the textual evidence, and I — assume for the moment I’m with you on the textual evidence. It’s close, okay? We’re not talking about extra-textual stuff. We’re — we’re talking about the text. It’s close. The judge finds it very close. At the end of the day, should he or she take into consideration the massive social upheaval that would be entailed in such a decision, and the possibility that — that Congress didn’t think about it — and that — that is more effective — more appropriate a legislative rather than a judicial function? That’s it. It’s a question of judicial modesty.

~ Justice Gorsuch in Harris Funeral Homes v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(with interruptions removed for readability)

Last week, in Bostock v. Clayton County and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Court addressed whether discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, respectively, is discrimination on the basis of sex, and thus contrary to Title VII. There has been much commentary on these cases; we are now able to take a look at the numbers, both to predict the outcomes of the cases based on the disagreement gap, and to empirically examine the content of some of the arguments.

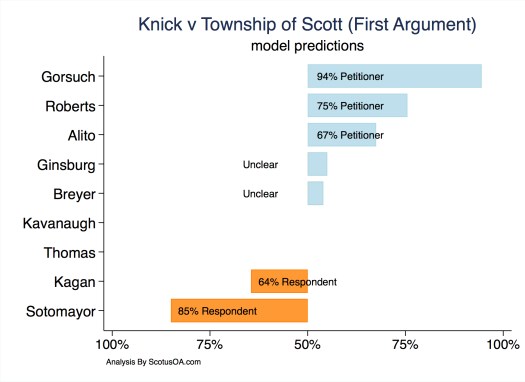

Our predictive model for Bostock shows Justice Alito clearly on the side of the respondent and Justice Ginsburg equally clearly on the side of the petitioner. The model is surprisingly equivocal about Roberts, Breyer, and Kavanaugh, and it suggests that Sotomayor, Kagan, and Gorsuch are leaning in favor of complainant petitioner. According to our model of Harris Funeral Homes, the justices lined up slightly differently in the transgender case. It shows Roberts and Gorsuch strongly in favor of petitioner (i.e. favoring a narrow reading of title VII) and Breyer, Kagan, and Ginsburg strongly favoring respondent. The model we use to predict votes based on oral argument is not particularly well suited to combined arguments, and this combined argument was especially confused. For example, the justices had multiple questions about bathrooms and gender identity for Pam Karlan in the first argument about the gay skydiver that would have made a lot more sense directed to David Cole in the second case about the transgender funeral home employee.

Others have suggested that Justice Gorsuch could be the potential swing vote in these cases. The reason for this is that, as a professed textualist, he could be expected to vote on the side of the Title VII plaintiffs, for whom the textual argument appears clear: if a woman who is married to or attracted to a man is treated differently to a man who is married to or attracted to a man, that would is clearly a difference based on sex. Similarly, if a woman who chooses to dress or identify as a man is treated differently to a man who chooses to dress or identify as a man, that is also a difference based on sex. Of course, as a conservative, Gorsuch’s ideological preferences pull him in the other direction. As such, these two cases are good tests of just how much of a textualist Gorsuch really is, or alternatively, how much of an ideologue. Our empirical analysis of the argument in Bostock v. Clayton County is encouraging for the plaintiff, but not in Harris Funeral Homes.

Of course, if Gorsuch votes to deny gay and transgender individuals the protection that Title VII’s plain text evidently affords them, he will not admit that he is not being a textualist. Rather, as the initial quote suggests, Gorsuch is claiming that the cases are very close, and that it is permissible to stray from textualism under such conditions. The word cloud pictured below is based on what Gorsuch had to say in Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC. It illustrates Gorsuch’s emphasis on the “close question” and signals that he is likely to vote for a narrow atextual reading of Title VII.

Text or pretext?

There are two massive problems with Gorsuch’s position: first his claim that the textualist case is a close one is implausible, and second, he is not asking the appropriate question.

First, the textualist argument on the other side is not simply weak; rather, it defies ordinary doctrinal logic. The argument goes that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity is not discrimination on the basis of sex because the question is: Is it lawful to treat a gay man differently to a gay woman, or a trans man differently to a trans woman? However, this phrasing of the question only works if you presuppose the answer to the question asked of the Court: whether using sexual orientation or gender identity as a basis for distinguishing is lawful under the statute. To phrase the question in terms of whether you are differentiating between different gay people in the right way presupposes that it is okay to treat gay women different to straight women, and gay men different to straight men. The textualist argument is not close; it is not even close to being close.

But the more damning problem is that a justice is not a textualist if he or she follows textualism only for the easy cases, and then if the case is “close” to the line, he or she can then turn to some other methodological approach to determine the difficult cases. The whole point of a judicial methodology is to apply it to differentiate between cases under and over the line. Looking to the text simply to ascertain whether a purported meaning is close enough to the penumbra of the text to justify then turning to purposivism to fill in the detail is contrary to the very notion of textualism. Put another way, it is not textualism if the key question is not what tool should be applied but rather when should the justice to apply it.

Consequently, gay and trans activists, and those who support them, placing their hopes on Gorsuch being true to his purported judicial ideology is likely to lead to disappointment. In fact, if Gorsuch is going to support that side of the arguments to any extent, the models make clear that it will be to support the gay complainants but to disappoint the trans complainants. This is in spite of the fact that the textual argument is much stronger in Harris than Bostock: the complainant in Bostock literally was fired for wearing a dress, which would have been permitted to anyone born a woman. The members of the Court, like much of society, have had more time to get used to the idea of people being gay than people being trans, and so find it easier to recognize and reject discrimination against gay people than trans people. To the extent Gorsuch will stray from his ideology, it would be in favor of the text but it will hinge more on that greater tolerance of gay people, and consequently greater tolerance of gender discrimination against trans people.

Prediction:

Title VII plaintiffs (Petitioner in Bostock, Respondent in Harris): Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan, Sotomayor

Title VII defendants: Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Roberts, and Thomas.

Most likely to switch: Gorsuch, but only in Bostock.

You must be logged in to post a comment.