Knick v. Township of Scott, Take #2

When the Supreme Court called for re-argument in Knick v. Township of Scott—on the metaphysical constitutional law question of exactly when a takings claim comes into being—it seemed likely that the Court had been set to split 4:4. The re-argument was presumed to be largely for the benefit of giving newly minted Justice Kavanaugh the power to cast the decisive vote.

A Clarifying Re-Argument

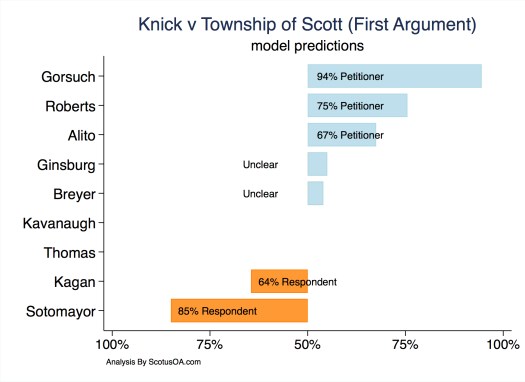

The re-argument in Knick v. Township of Scott was clarifying. So much so that we wonder whether every case should be argued twice! In our initial analysis of Knick, we predicted a 4:4 split, but there was considerable ambiguity about the position of a number of the justices, as the figure below replicates.

As we discuss below, the advocacy in Knick II was much better, to the point where even though we were still unconvinced by Petitioner’s advocate, J. David Bremer, we at least understood what he was trying to say this time. In addition to the advocates being clearer, the positions of the justices seemed to clarify a great deal.

Not surprisingly for a case pitting individual property rights against government regulation, our model of Knick II suggests a mostly liberal-conservative split. However, there are some interesting shifts from the first argument.

In particular, Justice Breyer has moved from the 50/50 column to the clearly pro-Respondent column, and Chief Justice Roberts appears to have switched sides entirely. Also, Justice Alito’s strong support for the Petitioner was clearer on the numbers in the second argument, although, as we had mentioned in our previous post, it was always clear in substance.

Despite his apparent switch, we are not sure we believe the model’s prediction for Roberts. He seemed to be asking pointed questions of Petitioner initially, but after some tough questioning of Breemer by Breyer, Roberts — like Alito in the initial argument — jumped in to help the advocate out by asking friendly “questions” and leading the discussion back on track.

We think Roberts is likely genuinely conflicted over this case. As the head of the federal judiciary, he has little interest in flooding the federal courts with state takings claims where federal judges will have to opine on state property law, yet he is philosophically inclined to a pro-property and anti-regulation position. We don’t expect the Chief to be as concerned for the “dignity and sovereignty of the States” in this case as he was in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). But then again, why a federalist would caste a cynical eye over the congressional record that repeatedly reauthorized the coverage formula for the Voting Rights Act, but then want to remove every mundane question of state property law to the federal courts, is hard to fathom.

Based on the substance of his questions and comments, we also think that the model may be overstating Breyer’s pro-Respondent leaning. Like Roberts, but for different reasons, Breyer was also conflicted about the issues presented in this case. Breyer was concerned for individuals caught in a Catch-22 situation created by the Court’s own precedent in Williamson County. Under Williamson County, the property owner who believes that a state regulation intruded upon her rights to such an extent that it constitutes a “regulatory taking” has no claim for the violation of her rights until she has pursued a claim for compensation in state court and been denied. This makes sense because the Takings Clause is violated not by takings as such, but by takings without just compensation. However, Williamson County creates a Catch-22 for plaintiffs because once they have argued their case in state court, the doctrine of issue preclusion prevents them from re-litigating the same takings question in federal court.

This Catch-22 obviously does not sit well with Breyer, but like Roberts, he is a pragmatist little attracted to the potential flood of premature local and state takings claims inundating the federal courts.

When this case was scheduled for reargument, it seemed inevitable that Justice Kavanaugh would cast the deciding vote. In theory, an ultra-conservative, Federalist Society approved justice would be expected to reflexively side with the property owner in a case like this, but Kavanaugh’s position was a little hard to read. When Justice Gorsuch was in a similar position in the Janus case, he said nothing. In Knick II, Justice Kavanaugh had quite a lot to say, but he seemed to have issues with both sides of the argument. Our model, estimates that he is 57% likely to vote for Respondent, but that is basically a toss-up.

Our Prediction

Justice Breyer spent much of the argument searching for a reasonable middle ground that would address the Williamson County Catch-22 without making the federal courts the first stop for every takings challenge to state and local government property regulations. We think that Breyer will hold that a takings claim is complete for the purposes of Section 1983 when a regulation goes into effect without a reasonable mechanism to determine whether compensation is owed, and that somehow the usual rules of issue preclusion will not apply to plaintiffs who exhaust their state remedies. How many votes this opinion will attract is far from certain, but we do think that the middle position of leaving Williamson County intact with some softening on issue preclusion might attract the votes of Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, Ginsburg, and just possibly Roberts and Kavanaugh. Alternatively, we could see multiple opinions. Justices Alito, Gorsuch, and Thomas are a lock for Petitioner.

Advocate Performance

As a final note, the next figure shows the cumulative word count for the justices as a group and for each advocate.

The comparison between Petitioner’s advocate and the Solicitor General who was also on the side of the Petitioner is quite telling. As we discussed in a previous post, the Court tends to give the Solicitor General and even state solicitors general much more deference than regular advocates. In this case, despite his improvement from Knick I, Breemer still struggled to get a few words in between the justices. In contrast, Gen. Francisco, who was exceptional in both arguments, was allowed to talk for the majority of his allotted 10 minutes. Sachs for Respondent was also very good in the second argument and seemed to get a reasonable chance to make the points she needed to make.

Prediction:

For Petitioner Knick: Alito, Gorsuch, Thomas, Kavanaugh

For Respondent Township of Scott: Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan, Roberts, Sotomayor

Most likely to switch: Kavanaugh, Roberts

You must be logged in to post a comment.