The two Eighth Amendment cases show hard cases make for hard predictions

Bad facts make bad law. So too, hard cases make for hard predictions. The Court’s two current death penalty cases, illustrate both phenomena. But these cases also illustrate the added value of empirical analysis of oral argument over purely qualitative or impressionistic readings.

The Supreme Court’s two current pending death penalty cases both have very peculiar facts. In Bucklew v. Precythe, argued last week, the prisoner argues that execution by lethal injection would be cruel and unusual given his particular medical history. Madison v. Alabama, argued on October 2nd, presents the question of whether a prisoner can be executed for a crime he cannot recall.

The Supreme Court had the option of taking a case raising a question with potentially much broader significance for Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. Hidalgo v. Arizona challenged whether Arizona’s death penalty legislation insufficiently narrowed application of the ultimate punishment. True to form, the Supreme Court avoided that important question of the frequency of the ultimate punishment, and focused instead on two cases raising as applied challenges, with limited applications for the 2,743 people currently on death row.

Forecast of Bucklew v. Precythe

Argument in Bucklew v. Precythe involved delving into the grisly facts of Petitioner’s medical condition and the painful possibilities involved in his execution. Along the way, the argument saw some unusual judicial behavior. Immediately, Justice Sotomayor began grilling Petitioner’s advocate for the lack of a clear record on those facts, and whether the horrific nature of his death could simply be avoided by the trach already installed in his throat.

Commentators on the First Mondays podcast suggested that this interplay may indicate that Petitioner’s advocate may have lost Justice Sotomayor, which would make it “tough” to win, given her general reliable pro-defendant vote. This much-qualified prediction misunderstands what is going on. Although Sotomayor was very active in questioning the Petitioner, and that level of activity often signals disagreement, she was even more active during Respondent’s time. Sotomayor spoke 17 times to Petitioner and 18 times to Respondent; but when she spoke to Respondent, she had much more to say—921 words versus 497 words. In spite of the opening salvo, by the end of the argument Sotomayor registered a significant disagreement gap in favor of Petitioner. Thus, even though she described herself as “upset” with Petitioner’s advocate, our analysis, represented in the figure below, predicts she is 90% likely to vote for Petitioner, and is the Justice most likely to do so.

Sotomayor normally reserves her toughest questions for the prosecution side in criminal cases—perhaps reflecting, as well as her liberal ideology, that as a former prosecutor herself she has particularly high standards for the profession. That fact made her sharp critique of the capital defendant seem more important than it really was. Our empirical approach to reviewing oral argument helps put episodes like this in a more balanced context and avoid salience bias (a recognized common behavioral irrationality that causes people to focus on prominent information and ignore potentially more significant but less noticeable contra-indicators).

A far clearer signal of a Justice breaking with expectations was Justice Kavanaugh. He spoke only to Respondent’s advocate and asked tough questions as to whether there was any limit on the potentially “gruesome and brutal pain” the state is permitted to impose in executing Bucklew, and demanded a yes or no answer from the state’s advocate.

In contrast, the numbers on Justice Gorsuch are likely misleading. He spoke only twice to Respondent’s advocate and once to Petitioner’s advocate, making his signals very weak. Equally importantly, both questions he put to Respondent’s advocate were open-ended questions asking him to get to a point he had said he would make—that is, a seemingly friendly inquiry. Given Gorsuch voted to deny the stay of execution, we expect he will join the other conservatives in voting with Respondent. (Although Justice Thomas was his normal reticent self, he too had joined the dissent from the stay of execution).

With Justice Ginsburg unusually silent (even before breaking her ribs), we can only go on her prior voting record, which is generally pro-defendant. All of this would lead to a prediction of a 5:4 vote for Petitioner, however the prediction depends on the untested vote of Justice Kavanaugh—a tough prediction, indeed.

Forecast of Madison v. Alabama

Oral argument in Madison v. Alabama, on the question of whether someone who cannot remember the crime he committed due to multiple strokes, also involved descriptions of peculiar facts. According to Petitioner’s advocate, inmate Madison regularly soils himself because he cannot remember that he has a toilet in his cell. The law on the issue was as messy as the facts. The following was a typical confused interaction:

Sonia Sotomayor: Mr. Stevenson, part of the problem is the use of the word “loss of memory.” And I — in your briefs, you seem to go back and forth on this. Are you conceding that amnesia about the incident alone, where you can function in every other way in society, would you be incompetent then?

Bryan A. Stevenson: No.

Sonia Sotomayor: To be executed?

Bryan A. Stevenson: Yes, that’s right.

On another point Justice Alito complained: “No, I don’t understand — I don’t understand your answer.”

And Chief Justice Roberts questioned whether there was an issue at all in the case, saying to Petitioner’s advocate: “There are two questions. You concede on one, and the state concedes on the other.” Petitioner had conceded that simply not remembering the crime is not enough to avoid execution, and the state had admitted that if the person is incompetent, they cannot be executed.

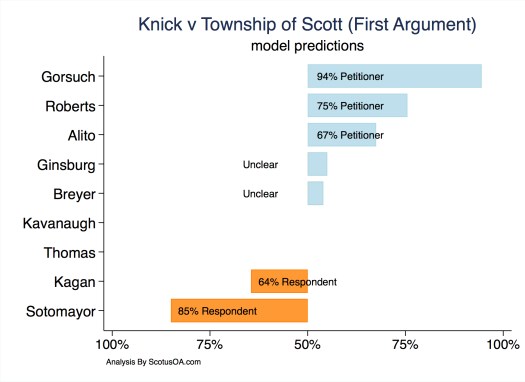

The figure below shows our predictions for the case.

Thomas was silent as always and Gorsuch was silent in this case also. Furthermore, both Breyer and Roberts presented ambiguous signals. Again, Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch had opposed the imposition of the stay, suggesting again support for Respondent. This time, however, Roberts had not joined that order. His far more mixed signal in this argument supports Amy Howe’s prediction that as Chief Justice, he “might have a greater incentive than his colleagues to avoid deadlocking on Madison’s case” (Kavanaugh was not yet on the Court when the case was heard) and so could provide the fifth vote for a very narrow victory for Madison by remanding the case back to state court to consider the specific question of whether Madison is incompetent because of his dementia.

We think this analysis makes sense of Roberts’ tentative signal. But we would go further and say that Roberts will only vote in favor of Petitioner for a very narrow ruling, otherwise he will vote for Respondent. We believe Roberts’ ambiguous signal indicates his concern over the potential for this second very specific medical circumstance to create an enormous slippery slope to a flood of future death penalty challenges. Whereas Bucklew’s case is limited to an n of approximately one, making it hard to justify the Court using one of its approximate 75 spots to effectively act as a court of last instance, in contrast, Madison’s case could drastically change death penalty jurisprudence. With death penalty appeals dragging the ordinary execution process out over decades, the chances of other inmates developing memory-related medical issues are very high. A broader ruling for Petitioner could spawn a tide of challenges that would make Atkins IQ challenges seem a narrow set. As such, we expect Roberts to either support a very narrow ruling for Petitioner or rule in favor of Respondent. The empirics indicate he is right on the borderline.

Thus, we predict a 5:3 win for Petitioner on narrow grounds, or a 4:4 default win for Respondent.

Prediction for Bucklew: 5:4 vote for Petitioner (Bucklew)

For Petitioner: Sotomayor, Kagan, Breyer, Kavanaugh, Ginsburg

For Respondent: Roberts, Alito, Thomas, Gorsuch

Most likely the switch: Kavanaugh

Prediction for Madison:

5:3 vote for Petitioner (Madison) and remand

or

4:4 vote for Respondent (Alabama)

For Petitioner: Sotomayor, Ginsburg, Kagan, Breyer, (Roberts)

For Respondent: Alito, Thomas, Gorsuch, (Roberts)

Most likely to switch: Roberts

You must be logged in to post a comment.