Gorsuch versus Kavanaugh: what is a conservative?

The Supreme Court heard two cases about the reach of the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA) in October that highlight stark differences between the two Trump appointees. Justice Gorsuch appears to be, as promised, a conservative in the mold of the late Justice Scalia: sitting far to the right on the Court but willing to side with the liberals when issues of methodology or fairness in criminal cases demand. In contrast, Justice Kavanaugh was uncritical of the potential harshness of the government’s position in each case, seemingly focused on promoting the law and order outcome rather than refining the means of analysis.

The two cases involve complex distinctions about the applicability of the much-litigated ACCA, which imposes a 15 year sentence enhancement for persons convicted of three crimes within certain specified categories, at least one of which involves weaponry. Burglary is one recognized category, and U.S. v. Stitt queries whether burglary of a residence can include burglary of a vehicle—which previous cases have said are otherwise not covered—if those vehicles can be adapted for residency or are otherwise being used as residences. Robbery is not recognized as a category under the ACCA, but Stokeling v. U.S. raises the question of whether robbery can nevertheless be covered by the sentence enhancement as a crime that has “an element of use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force” against another, even if it only involves using slight force to overcome minimal victim resistance.

Early in the argument in Stitt, Gorsuch started listing problems with the government’s position, drawing on a variety of approaches, from textualism—including drawing significance from the state legislature’s use of a disjunctive and the government’s interpretation raising problems of surplusage—to whether congressional intent could be inferred if the legislation covered so few states that defined burglary in such a way. He made similar points in Stokeling, along with raising concerns about the meaning of the legislation at the time of enactment, the traditional use of the term ‘robbery’ at common law, as well as more general critiques in Stitt about widely held dissatisfaction with the Court’s jurisprudence on the ACCA.

In contrast, Kavanaugh focused on carefully maneuvering around prior precedent to make a stronger case for the government. For instance, in Stitt, he appeared quite well-prepared, tailoring a path for getting around what had appeared to be a bright line rule against the inclusion of vehicles in burglaries. For a number of justices, ACCA cases raise questions of fairness, notice, due process, and proportionality, as well as difficult questions of statutory interpretation. Kavanaugh seemed unfazed by these worries, saying for instance of the notice question: “if you’re convicted three times of burglary for burglarizing an RV, you’re on notice, presumably. . . I don’t understand the notice point.”

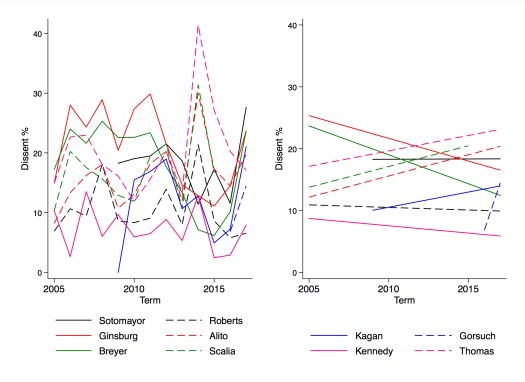

These differences are likely to be determinative, and we predict that the two Trump appointees will diverge in their votes on these two cases, as the following two figures show.

Figure 2

The figures above show the results of a new predictive model we have developed. The model transforms statistical observations about oral argument directly into predicted probabilities based on the prior behavior and voting patterns of each justice. We blended an average of Gorsuch, Roberts, and Alito for the 2017 Term to estimate baseline parameters for the newly appointed Kavanaugh.

In Stokeling (the robbery case), the model predicts a winning coalition for the Petitioner (the criminal defendant) of Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, and Ginsburg, with probabilities of 88%, 87%, 84%, and 68% respectively. Justice Breyer was uncharacteristically silent but we are somewhat confident he will make up the fifth vote (Breyer is only silent in about 7% of arguments). The model predicts at least a three justice minority consisting of Justice Alito, Chief Justice Roberts, and Kavanaugh, with 91%, 66%, and 61%, respectively. These numbers struck us as understatements after we listened to the argument.

In Stitt (the burglary case), we believe that the Chief and Justice Thomas will vote for the Petitioner (the state), although Thomas said nothing and Roberts said nothing of substance during the oral argument. Assuming Roberts will vote consistently in the two cases and that Thomas will vote against the defendant in both, the model predicts a winning coalition of Kavanaugh, Kagan, Alito, Roberts, and Thomas, at rates of 88%, 73%, and 58% for Kavanaugh, Kagan, and Alito, respectively. The model also predicts at least a three justice minority consisting of Ginsburg, Gorsuch, and Sotomayor (all north of 85%), but it is equivocal about Breyer, as indicated by the fact that he shows up on both sides of the 50/50 dividing line.

One of the striking aspects of the two arguments is that Justice Kagan seems likely to vote a split ticket, holding for the criminal defendant in one case and for the government in the other. For Kagan, the central question in both cases appeared to be the feasibility of line-drawing. The difference between the two cases is that Kagan appeared comfortable with the distinction between mobile homes and other vehicles in Stitt, but not with the different shades of robbery implemented by the various states in Stokeling. It is also possible that Breyer will split the same way for largely the same reasons, but this is far from clear from his numbers. We expect the rest of the justices to vote consistently pro- or anti-criminal defendant in both cases.

Stokeling prediction: 5:4 for Petitioner (Stokeling)

For Stokeling: Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, Ginsburg, and Breyer

For the government: Alito, Chief Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Thomas

Most likely to switch: Breyer

Stitt prediction: : 5:4 for Petitioner (the state)

For the government: Kavanaugh, Kagan, Alito, Roberts, and Thomas

For Stitt: Ginsburg, Gorsuch, Sotomayor, and Breyer

Most likely to switch: Breyer

You must be logged in to post a comment.