Oral argument as a preview to dissents

For a case to reach the U.S. Supreme Court, it should present a difficult question of law. The Supreme Court is not the ultimate arbitrator of fact but rather the apex court with the responsibility of determining the most pressing questions of doctrine. Reflecting this, the justices give priority to cases that represent circuit splits in the lower courts. Accordingly, it is unsurprising that in about 60% of cases at least one justice dissents. But the distribution of dissenting votes is far from uniform. Who dissents the most at the Court?

Click Image to Expand

The figure above shows the justices ranked by their relative percent of dissenting votes. On the Roberts Court, Justice Ginsburg dissents the most often, followed closely by Justice Thomas. At the lowest end of the spectrum lies Justice Kennedy, followed by Chief Justice Roberts.

Overall rate of dissent rate is not same as the number of dissents. Ginsburg, for example, has a dissent rate of 19.55% for her 25 terms on the Court. During this time she decided 2092 cases, 1664 in the majority and 409 in dissent. Ginsburg’s dissent rate is slightly ahead of Thomas’ (18.96%), but with his two year head start, he actually has more total dissents (442). Neither Ginsburg nor Thomas are anywhere near Justice Stevens’ 1054 dissents at an average of 24.69%.

The big picture pattern that emerges is straightforward: Justice Ginsburg is the most extreme liberal on the current Court, Justice Thomas the most extreme conservative; Justice Kennedy was the Roberts Court median, and he is expected to be replaced in that role by the Chief. Looking to previous eras, the same pattern holds: Justice Douglas was the most extreme justice on the Court since Martin and Quinn started measuring judicial ideology, followed by Justice Marshall (although Justice Harlan was somewhat more moderate). And not only were the other lowest dissenters, Justices Goldberg and Powell, also Court medians, but along with Justice Kennedy, all three were “super medians”— justices who dominated the center of the Court.

This is not a coincidence: the dominant measure of judicial ideology, the Martin-Quinn scores, hinge on dissenting as a sign of extremism. Essentially, the scores are based on the idea that the more often a justice dissents alone, the more extreme he or she is likely to be; the more often a justice votes with other justices, the less extreme he or she is likely to be. Moderates tend to find common ground with others, extremists do not. Consequently, looking at dissent rates over time reveals interesting insights into the changing dynamics of the Court.

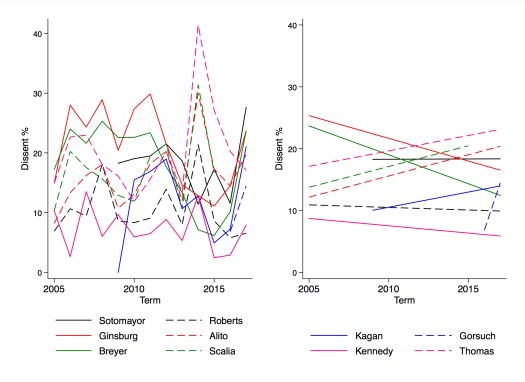

Click Image to Expand

The above figures both show the dissenting rates for each justice over time—the figure on the left shows the full variation for each, the figure on the right shows the trend for each justice over time. It is clear that while Justice Ginsburg has the highest rate of dissenting on the Roberts Court, that has not been true for the last five years. Both she and Justice Breyer have dissented less in recent years, while at the same time Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito have increased their rates of dissent. This conclusion adds to the significance of the reputedly more consistently conservative Judge Kavanagh potentially replacing Justice Kennedy: we can expect a resurgence in dissents from the justice so often celebrated for her dissents, Justice Ginsburg.

The reason is clear: Justice Kennedy sided more with the liberal justices in recent years than previously. This occurred frequently enough that in the 2014, 2015, and 2016 Terms— although not in his final term— Justice Kennedy measured as negative, i.e. slightly liberal in historical terms, whereas previously he had always registered as moderately conservative. The zero threshold is somewhat artificial but Kennedy’s relative liberal decision-making in his final years is reinforced by the increasing dissent rate of Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito. The lack of a similar pattern by the Chief supports the view that this is a product more of the changing agenda of the Court than any actual change in preferences by Kennedy prior to his retirement—it seems that the Court was taking more cases where moderate conservatives have more in common with liberals than with extreme conservatives.

The limit of ideological measures is that they are based on judicial votes in cases by Term—thus they are both retrospective, knowable only after the justices have determined case outcomes, and are also generalized trends. But we know that the justices sometimes vote contrary to their ideology, so to predict case outcomes, ideally we would have ex ante case-specific information, rather than ex post Term-level information. And this is where oral arguments come in.

The justices’ dissenting behavior follows a pattern discernible not only from long-term trends, but also from individual case behavior: how much they speak at oral argument. The following table shows the trend for the Roberts Court; the same pattern has been shown to apply for previous courts.

Words Spoken in Majority and Dissent on the Roberts Court

| Justice | Words in Majority (average) | Words in Dissent (average) | Dissent-Majority Difference | Dissent-Average Difference | ||

| Gorsuch | 313 | 514 | 201 | 66 | ||

| Thomas | 57 | 203 | 146 | 87 | ||

| Souter | 581 | 715 | 133 | 104 | ||

| Alito | 323 | 441 | 117 | 86 | ||

| Scalia | 592 | 677 | 84 | 72 | ||

| Kennedy | 320 | 384 | 63 | 64 | ||

| Kagan | 553 | 607 | 54 | 35 | ||

| Breyer | 823 | 874 | 51 | 34 | ||

| Stevens | 282 | 329 | 46 | 30 | ||

| Roberts | 542 | 580 | 38 | 38 | ||

| Ginsburg | 430 | 455 | 25 | 27 | ||

| Sotomayor | 536 | 546 | 9 | -11 |

The above table shows the average number of words used by each justice per case at oral argument when the justice is ultimately in the majority once the case is determined, and when ultimately in dissent. The difference for every justice is positive: justices consistently speak more when they will ultimately dissent in the case. When normalized for the amount of words each justice speaks on average per case, the difference is positive for every justice except for Justice Sotomayor. As such, with one exception, if you want to know whether a justice is likely to dissent in a case, you need only listen carefully to how much they talk at oral argument and compare it to how often they ordinarily talk. The most talkative justices will, on average, be those who ultimately dissent. This comports with the more general trend we have shown that the “losers of history”—be it in the case at hand or in terms of long-term dominance of the Court—tend to be more active at oral argument than those on a winning streak.

In this way, as in others previously explored, oral arguments can constitute a preview of case outcomes, including which justices will dissent. This is particularly helpful when we have less information from other sources. As we have previously cautioned, analysis of Justice Gorsuch’s behavior has to be particularly careful because of his short service on the Court. The first figure suggested that Justice Gorsuch may be less conservative than expected, sitting as he does in his initial rate of dissent between Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito. But his high level of difference in activity level when dissenting versus when in the majority puts him in a far more extremist company, with strongly conservative Justices Thomas, Alito, and Scalia, as well as Justice Souter, who, despite being appointed by a Republican, was almost as liberal as Justice Ginsburg.

You must be logged in to post a comment.